Marks on Paper

- Double Haul

- Jan 8

- 3 min read

In my first year at U of T in the Faculty of Forestry, we had a course in dendrology. Dendrology includes the learning of how to identify plant species based on features like leaves, bark, cones flowers and fruit. Even today I remember that Scots pine has twisted needles in bundles of two and white pine have needles in groups of five. I can tell a spruce from a fir by the sharpness of the needles. It was a class I enjoyed and excelled at. I think it has something to do with my inherent powers of observation and fascination with the details of things.

Now, forty plus years later, this same appeal is showing up in my pen and ink drawings. Accurately capturing the particulars of objects is an important part of my journey towards a faithful, still far from flawless, representation.

I count the scales; I make sure the leaves are oppositely (or alternately) arranged as required. I look to understand the construction of a thing whether it’s a sunflower or a pair of binoculars.

The teaching assistant assigned to our class, once looked at the sketches in my notebooks and remarked that I should have been an artist. It’s become an anecdote in my life, that predated a quick switch from pursuing a BScF degree to an application to the Ontario College of Art. I had never taken an art course in high school. It was three maths, physics, biology and chemistry. My portfolio review when I applied included some drawing, but it was the Photo Electric Art program that I had set my sights on, so I relied more on my black and white photography which by that time had led me to setting up a darkroom in the basement. The program was technology heavy and encompassed photography, film, video and computers. The first year of our studies was a foundation year and we did life drawing, 2D design and colour theory. Later I would build an Apple IIE clone computer and use circuitry for installation pieces. I still remember the day a Mac arrived with desktop publishing software and the early impression that something was brewing. It was still before widespread adoption of the internet and computer before that were mainly controllers of some device or an instrument of measurement. If I had been in that program a decade later, I would likely have become a web designer.

My own path post-college took me into commercial television and advertising. I put more energy into photography and video both at my job and in my spare time, but I still carried a sketchbook for those times when I wanted to slow down and be absorbed into observation.

After my retirement, I found I had more time for creative pursuits. Printmaking and drawing caught my interest early. I find lino cut and etching both satisfying for their physical effort and the familiar process of making a mark on something or, in the case of block printing, carving away a space.

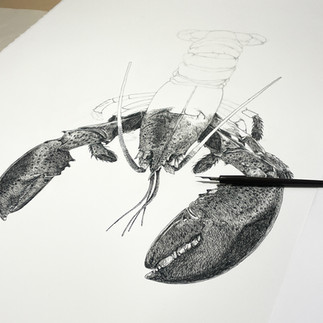

My dip pen drawings capture objects in large scale. Marks on paper that hint at details and reveal an understanding of the subject accumulated through careful observation. There is no obvious agenda or manifest. Consequently, there is a great emphasis placed on technique. The execution is initially what people seem to dwell on.

They are familiar and generic. But they are purposefully chosen and given prominence. These are things we might likely have our own interactions with, or some fluency in their language. Because there is an obvious commitment to creating them, it brings into question how they are connected to me. Are they reminders of history, a place, or an experience?

The objects themselves float in space, without the interference of background or anchored in the construction of setting. There are no distractions. They exist unconnected. Against the stark white of the paper, there is no escape from examination. Their size is understood without the need for any juxtaposition.

Time is both implied and made explicit. In the case of living things, we understand that they are transitory. Blooms will fade; leaves will wilt. Other objects are old and carry the scars of their use. The process of making overtly reflects time as well. The layers of cross hatching and fine individual lines make it clear that hours have been invested.

Comments